Quick Summary

- Professor Olmsted discusses her latest book: The Newspaper Axis

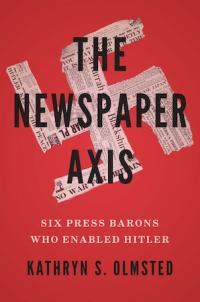

This blog highlights and summarizes an article by Raw Story. It comments on The Newspaper Axis: Six Press Barons Who Enabled Hitler by Kathryn Olmstead, professor of History at UC Davis. You can access the full article here. This blog also quotes a talk Olmstead gave at the Roosevelt Reading Festival. Listen to the talk on C-SPAN here.

In our hazy collective memory about Franklin Roosevelt, the Great Depression and the march toward World War II in the 1930s, we sometimes assume the people of the United States were absorbing the printed and broadcasted words of an objective and fair news media.

Nothing could be farther from the truth, as University of California, Davis, history professor Kathryn S. Olmsted ably proves in her deeply researched book The Newspaper Axis: Six Press Barons Who Enabled Hitler. Not only were some of the foremost newspaper publishers of the day needling FDR with stilettos on their editorial pages, but they also even imposed their views on their reporters. “Fake news” was as evident in those days as it is today.

FDR was opposed on both the domestic and foreign fronts during most of his time in office by the press lords Willam Randolph Hearst, owner of a network of newspapers and radio stations whose motto was “America First,” and Col. Robert McCormick, publisher of the Chicago Tribune, the self-proclaimed “world’s greatest newspaper.” While initially supportive, McCormick’s cousins, siblings Joseph and Eleanor “Cissy” Patterson, eventually turned on FDR too. Joe Patterson published the largest circulation newspaper in the country, the New York Daily News, while Cissy published the largest circulation newspaper in Washington, the Times-Herald. As a group, they reached 30 percent of the American newspaper-reading public every day.

“They used their papers to proselytize for nationalism, appeasement, and isolation. So, estimating four readers per copy, which is what auditors did at the time, The McCormack Paterson Press reached more than 12 million Americans daily and 20 million on Sundays. Now, by contrast, the newspapers and magazines that supported Roosevelt’s internationalist foreign policy had far fewer readers. The most important outlets that were internationalists were Time Magazine, The New Yorker, Herald, Tribune and the New York Times. And collectively they reached less than a quarter of the Hearst-Patterson-McCormick Sunday readership,” said Olmstead in a talk held at the Roosevelt Reading Festival.

McCormick’s vitriol easily matched that of the better-known Hearst. He called the New Deal the “Raw Deal” and instructed his White House correspondent to label the federal work relief programs “government easy money.” When the Lend-Lease bill was debated by Congress in 1940, the Chicago Tribune called it “the Dictator Bill” in all its coverage — without using quotes around the mocking nickname. McCormick was convinced that every Roosevelt program and action was designed to make him the country’s dictator, but he was willing to give a true dictator like Hitler a pass because of his own fierce isolationism and hatred of communism. Apparently, a fascist dictator trumped a communist one.

“They believed that Roosevelt wanted to aid Hitler’s enemies, not because he feared for US Security, not because he sympathized with the victims of facist aggression, but because he believed that a war would give him the opportunity to seize total control of the government and democracy, cancel elections and start his own dynasty,” Olmstead said.

FDR and his supporters were able to neutralize some of the power of Hearst, McCormick and the Pattersons regarding Lend-Lease and the need to rearm the country with tools such as FDR’s Fireside Chats over the radio and the growing popularity of commercial radio and motion pictures.

It was a way of going over the heads of the press parents and talking directly to Americans. In one Fireside Chat, for example, he said that the war effort must not be impeded by, ‘A few bogus patriots who used the secret sacred freedom of the press to echo the sentiments of the propaganda in Tokyo and Berlin.” — Olmstead.

After the fall of France in June 1940, Hollywood began producing more anti-Hitler films, especially those vilifying the Nazis and praising the English. They included Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent and Daryl Zanuck’s A Yank in the RAF.

Olmsted deftly interweaves the stories of the conservative press in the two countries through the 1930s and beyond. Although Lord Beaverbrook, a powerful press lord in England who worked closely with Heart, McCormick, and the Pattersons, took major posts over war production in Churchill’s government, after the war he reverted to type, opposing the Marshall Plan, the United Nations and the European Common Market. Olmsted notes that Rupert Murdoch, who went on to found Fox News, was a protege of Beaverbrook’s in the 1950s. He learned at the knee of a master and helped engineer Brexit.

She concludes her powerful book with this eloquent paragraph:

“We can still hear the echoes of their voices today — in the anti-European headlines of the [British] Daily Express and the Daily Mail, in the angry populism of Fox News and Breitbart, in the nationalist speeches of Boris Johnson and Donald Trump. ‘From this day forward a new vision will govern our land,’ President Trump promised in his inauguration address. ‘From this day forward, it’s going to be only America First — America First.’ The last of the press lords died more than a half century ago, but their heirs continue their crusade for nation, for empire, for the ‘white race,’ and for Britain and America First.”

Media Resources

Media contact:

- Karen Nikos-Rose, kmnikos@ucdavis.edu