Plants have resources, and bacteria want them. Plants have gates on their leaves to keep the thieves out. But a nasty bug called Salmonella has figured out how to trick plants into opening up their safety gates so it can sneak in and live happily inside.

When people eat those contaminated leaves, they can get sick, sometimes severely. Because the bacteria are actually inside the leaves, they cannot be removed by washing.

Now, researchers at UC Davis have figured out how Salmonella does its dirty work. Plants close their safety gates (stomata) when they detect the invader. But the bug somehow induces the production of a hormone called auxin, which gives a kind of false “all-clear” signal that causes the plant to open its gates and let the invaders in.

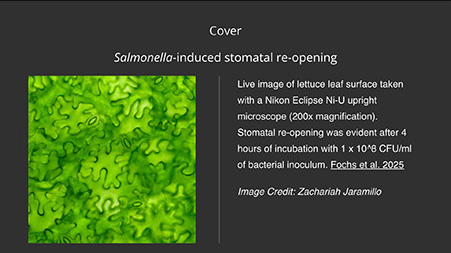

The discovery by a team led by Maeli Melotto, a professor in the UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences, is good news for efforts to breed lettuce and other leafy greens resistant to sneaky microbes. Their research was featured on the cover of the prestigious open-access journal PLOS Pathogens. The lead author is Brianna Fochs, who was a Ph.D. student in Melotto’s lab and has since graduated.

Most of their research was done in the model plant Arabidopsis, but the mechanism is similar for lettuce, spinach, basil and other crops. Infected greens are the source of more than 9 percent of foodborne illnesses across the country, sickening an estimated 2.3 million people and costing up to $5.3 billion every year.

“We are now a step closer to translating this knowledge to leafy greens and start breeding for safer crops,” Melotto said. “But additional research is needed to solve the problem.”

Auxin opens the gate

Stomata are tiny pores on the surface of leaves which open and close for all sorts of fundamental plant processes. When plants detect bacterial flagella, the hair-like propellor some bacteria use to move, they respond by closing the stomata. The stomata reopen a few hours later, in response to the plant hormone auxin. Some strains of Salmonella bacteria are able to reopen the stomata. Melotto’s team has now found that both bacteria and host plants are involved in producing auxin to reopen the stomata.

It’s not clear how biosynthesis of auxin is triggered, nor who is triggering it: Both plant and bacterium produce the hormone, Melotto said. The chemical pathway also remains a mystery – for now.

The team included graduate student Zachariah Jaramillo, who took the winning cover photo. Jirachaya Yeemin used a range of technologies to identify and quantify molecules involved in the plant-bacterium interaction. Jaramillo and Ho-Wen Yang conducted additional experiments to validate Fochs’ results.

Funding for this research came largely from National Institute of Food and Agriculture, part of the United States Department of Agriculture. One of the institute’s priority research areas is breeding food crops for greater safety.

Media Resources

Adapted from this article: War at the Stomatal gate: Melotto Team Flags Chemical Signaling that Tricks Plants (Department of Plant Sciences)

Salmonella enterica exploits the auxin signaling pathway to overcome stomatal immunity (PLOS Pathogens)

Trina Kleist is a communications specialist with the UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences.