Take a stroll down the middle aisles of any American grocery store, and you’ll be surrounded by rows of brightly colored packaged macaroni and cheese, instant soups and chips in all forms and flavors — all with long ingredient lists. These and other familiar favorites offer consumers a convenient, tasty and often affordable meal or snack.

Studies suggest, however, that nearly two-thirds of the average American diet consists of highly processed or “ultra-processed” foods. And growing scientific scrutiny and public concern are forcing policymakers to take a closer look at what these foods are — and what they may be doing to our health.

“We’re creating ingredients so rapidly, we don’t have time to study them,” said Alyson Mitchell, a professor and food chemist in the UC Davis Department of Food Science and Technology. “The food technology has moved faster than the health studies have.”

Adding to the uncertainty, there's no consensus about what “processed food” is, said Charlotte Biltekoff, a professor of American studies and food science and technology at UC Davis. In her book, Real Food, Real Facts: Processed Food and the Politics of Knowledge (University of California Press, 2024), Biltekoff explores the tension between consumer perceptions and the food industry's framing of processed food.

“Sometimes 'processed' is used very generally to refer to 'bad' food,” Biltekoff said.

She said when people talk about it in this way, they are usually referring to ultra-processed foods.

“Other times it’s used technically to describe a manufacturing process.” These different frameworks create confusion about what the term really means.

To cut through the confusion, Brazilian researchers in 2009 developed the NOVA classification system that catalogs foods by the extent and purpose of industrial processing:

- Category 1: Unprocessed or minimally processed foods — such as whole foods, vegetables, fruit, meat and pasta. These foods may have been washed, dried, frozen or vacuum-packed but have no added ingredients.

- Category 2: Culinary ingredients that have been processed, including oil, butter, sugar or salt. They are typically used only in cooking and not eaten on their own.

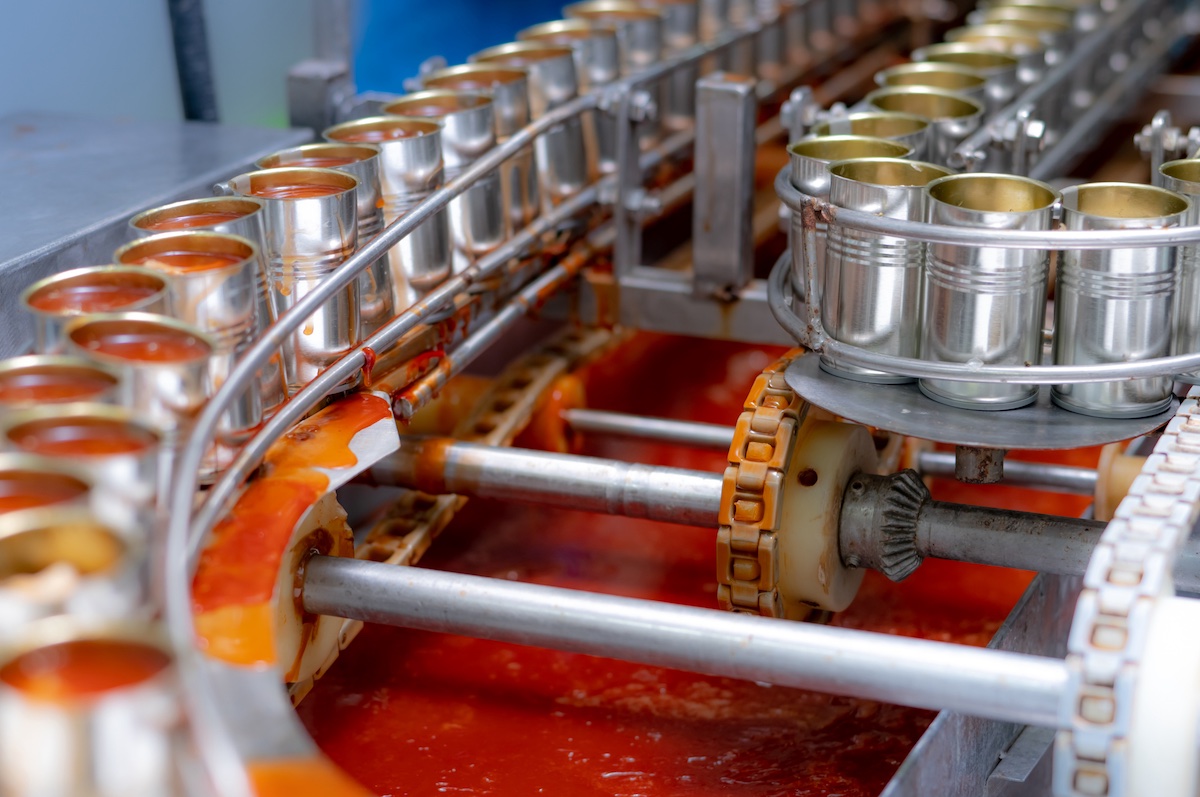

- Category 3: Processed foods — made by combining Category 1 and 2 foods through preservation or cooking. Examples include canned tuna, fruits in syrup and salted nuts.

- Category 4: Ultra-processed foods are industrial formulations made from food components. They include additives that are rare or nonexistent in culinary use, like emulsifiers, hydrogenated oils, synthetic colors, texture improvers or flavor enhancers. Think chips, soda, instant soup, pastries and mass-produced breads.

It’s the last category — ultra-processed foods — that has raised flags.

“A lot of the technologies that we’re using are restructuring molecules and creating molecules that we’ve never been exposed to before,” Mitchell said.

She said ultra-processed foods are not so much foods as they are formulations of foods designed to make the product more appetizing so you’ll buy more of it.

“The purpose is not necessarily to improve safety or improve the shelf life of the food,” Mitchell said. “It’s to sell a food product. It’s to make money off the food.”

Are ultra-processed foods 'bad' for you?

While more than 20,000 studies have examined ultra-processed foods, the vast majority have been observational. These studies report an association — but no causation — between eating ultra-processed foods and obesity, cardiovascular disease, some cancers, depression and gastrointestinal disorders, said Angela Zivkovic, an associate professor in the UC Davis Department of Nutrition.

“We have no way of telling whether the disease outcome is due to the intake of that food or whether it is a reflection of an overall diet and lifestyle,” Zivkovic said.

For example, people who eat more ultra-processed foods may also drink more sugar-sweetened beverages, be less active, or eat fewer fruits and vegetables.

Zivkovic said the handful of studies that have evaluated the direct effects of ultra-processed foods have shown they lead to higher consumption of calories and weight gain. Even when diets were matched for carbohydrates, protein, fat and fiber, participants consuming more ultra-processed foods consistently ate more calories and gained more weight. These findings suggest that something about ultra-processed food encourages overeating and may contribute to weight gain.

She added that ultra-processed food is not just dense in calories but also poor in nutrients.

“When you eat these foods, you have consumed calories but not any of the rest of what you need to be getting out of your food to sustain all of the various processes that the body needs to perform,” Zivkovic said.

Zivkovic said this calorie-dense, nutrient-poor combination could increase the risk of a variety of diseases, but it’s also possible that certain ingredients in ultra-processed foods — synthetic colors, flavors, stabilizers, preservatives — could also play a role.

If a consumer were to eat just one snack-sized bag of chips a month, there might be very few, if any, health implications, according to Zivkovic. But she said eating a one-pound bag of chips twice a day, every day, could expose consumers to a potentially serious dose of chemicals that could affect their health.

Prevalence of food dyes

Synthetic food dyes are commonly found in ultra-processed foods. Mitchell, who specializes in food chemistry and toxicology, points to a collaborative study with California’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, which found links between synthetic food dyes and neurobehavioral problems, such as hyperactivity, in some children.

The research also showed that children are exposed to multiple dyes in a day, meaning children could be getting exposed to food dyes that exceed the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s acceptable daily intake levels. Mitchell said many food coloring agents once found in ultra-processed foods were derived from coal tar dyes. Those found to be carcinogenic have been taken off the market.

“Only seven food dyes are allowed in foods anymore because we know they're problematic," Mitchell said. "They do not belong in our foods. They serve the food industry — not the consumer.”

3 Experts Weigh In on Processed Foods

UC Davis researchers offer insights based on research.

Not all ultra-processed foods are inherently bad. Mitchell said there are valid reasons to develop shelf-stable, industrially produced foods — for example infant formula, meals for astronauts in space and emergency rations in war or disaster zones. The issue is when those technologies become the norm rather than the exception.

Mitchell said more regulation or restrictions may be warranted until scientists can better understand the health effects of ultra-processed food.

Why the debate won’t go away

Processed food is not just a scientific issue; it’s also a cultural and political one. Biltekoff said public anxiety over processed food often stems from broader concerns about the food system itself.

“Many consumers worry about processed foods’ effect on individual or population health, their effect on the environment, but more broadly they see them as troubled products of a troubled food system,” she said.

As Biltekoff argues in her book, the food industry tends to attribute consumer anxieties over processed foods to misunderstanding and attempts to counter those fears with scientific facts or by rebranding products to make them appear more natural with shorter and more pronounceable ingredient lists.

But Biltekoff said correcting the public with facts misses the point.

“Instead of focusing so much on the problem of public misunderstanding, let’s change the perspective and think about the problem of experts' misunderstanding of the public.”

Biltekoff argues that the public wants to be engaged in big questions about the trajectory of the food system.

California lawmakers are debating whether they should phase out some ultra-processed foods in public schools. They’ve already banned several artificial food dyes from meals, drinks and snacks served in public schools. U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has also cited “highly chemically processed foods” as a chief culprit behind an epidemic of chronic disease in the United States.

Ultimately, Biltekoff said, the debate over processed food is about more than ingredients. It’s about how we define food itself — what we expect from it, how we regulate it, and who we trust to shape its future.

Media Resources

Media contacts:

- Amy Quinton, News and Media Relations, amquinton@ucdavis.edu, 530-601-8077